No matter how busy Collingwood gets, no matter the volume of the latest festival or event, and despite the general noise of hustle and bustle, there’s one sound missing, its absence a reminder of the changes time has brought.

The shipyard whistle sounded six times a day every day there were workers at the docks. The blasts began at 8 a.m. for the first shift, then for lunch at noon and the end of the shift at 5 p.m. The next shift started at 5:30 p.m. with another toot lunch at 9:30 p.m., and shift’s end at 2:30 a.m.

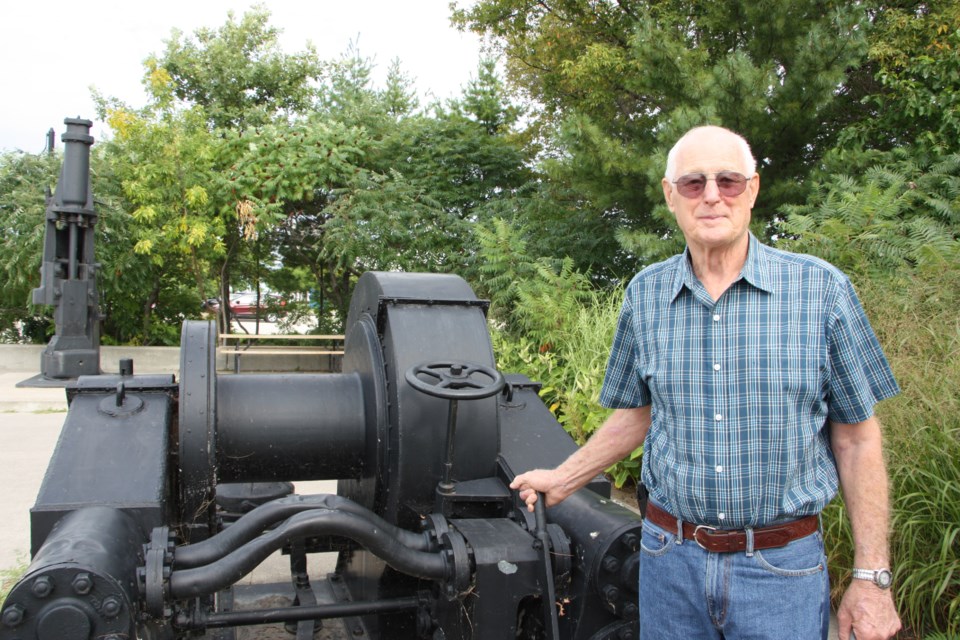

Barry Underdown heard those whistles from the day he was born in his parent's apartment on First Street (today it’s Ashanti Coffee).

“From the first breath I drew, I heard the shipyards whistle,” said Underdown. “I would dearly love to hear that whistle again.”

He was the last employee of the Collingwood shipyards, ending his more than 30 years as an employee with guard duty in the 1990s. Initially, he stayed on to dismantle shipbuilding equipment, take down cranes and send parts to other shipbuilding operations around Canada. Later, he patrolled the vacant buildings at night on his own, armed with a flashlight to prevent thieving and vandalism.

As a child, Underdown visited the blacksmith shop at the shipyards where his father and uncle worked. His father was blacksmith foreman and could operate a machine hammer with such precision he would practice placing an egg on the block and bringing the hammer down to touch but not break the egg.

Trips to the shipyards where his father and Grandfather worked were as much a part of Underdown’s childhood as the sight of a ship's bow at the top of Hurontario Street. He joined crowds of people to watch the side launches and he lived his days without need of a watch, listening for the shipyard whistle.

He didn't go east of Hurontario Street and heard tales of the "hobo jungle" on the East side. He helped deliver bread with Jack Pearce and milk for Keith's Dairy.

"Those were kinder, gentler times," he said.

Underdown was hired at the Collingwood Shipyards in 1962 as part of the Riggers crew. Those were the workers tasked with moving heavy items from the docks to the ship or back via cranes.

In the 1970s there were about 1,200 employees at the Collingwood shipyards, all assigned to various crews: riggers, welders, fitters, blacksmiths, electricians and more.

“It was quite a place for practical jokes,” said Underdown. “There will never be another place like it.”

On side launch days, excitement was palpable. Busloads of enthusiasts arrived from places like Michigan to watch a great ship be tossed into Collingwood’s harbour on its side, dipping into the dark water and bobbing back upright – a metal mass swaying violently back and forth as workers scurried to settle its rocking.

“On launch day I would wake up in the morning and I’d have tingles in my spine,” said Underdown. “There was a feeling of electricity in the air.”

Ships were usually launched at noon, so the anticipation built all morning.

Members of each crew climbed on board the ship to “ride it in” during the side launch. Each had different jobs. The riggers operated winches meant to quell the ships swaying.

The first ship Underdown rode in was the Simcoe.

“These guys had me so scared,” said Underdown. “I bet my fingerprints are still in the bulwarks of that ship.”

But it went off without a hitch, which cannot be said for the side launch of the Tadoussac.

Underdown was climbing a ladder to board the Tadoussac on May 29, 1969, when he heard someone shout. The ship was slipping into the water prematurely.

“I got over the side and to the winch and looked aft and she was gone,” said Underdown. He was safe aboard the ship.

The Tadoussac launched 15 minutes early, before preparations were complete and the workers safely out of the way. Two shipyard workers were killed and 40 others were injured.

Underdown watched his fellow shipbuilders being hit with timbers, chains and water as the momentum of the ship carried it toward the water and pulled everything with it.

“I will never forget that as long as I live,” said Underdown. “If I close my eyes tightly I can still feel the deck of the Tadoussac under my feet.”

He didn’t get off the ship until late that afternoon. He walked up Maple Street on his way home to his young wife and met his father on the road.

“He just looked at me and told me to phone my mother when I got to the house to let her know I was OK,” said Underdown.

His wife was frantic when he arrived at their apartment.

“Not just her, every wife was frantic,” said Underdown. “Some of the guys ran out of the shipyards gate with their hammers still in their hand … it was terrible.”

In 1980, Underdown was promoted to Berth Master, which meant he coordinated all the work done by the shipyards four Berth cranes.

In the height of production, once a crew finished work for the ship in the dock, it would start work on fabricating units for the next build. On launch day, when the ship was clear, the docks were cleaned up and organized for building to begin again. Working far ahead meant there were no layoffs, all the trades could keep working.

In 1983, work began on what is now Mariner’s Haven development, started by William (Bill) H. Kaufman. Underdown recalls looking across the harbour as crews worked to build homes within sight of the shipyards.

“I thought, ‘this is not going to work, condos over there and a whistle here at 2:30 a.m.’” said Underdown. “It started to make you think.”

On Sept. 12, 1986, the shipyards closed with a final whistle.

“I think everybody was pretty numb,” said Underdown. “They were wondering, ‘what’s next?’ and ‘where do I go from here.’ In a lot of cases, it was all people had ever known.”

“[Collingwood Shipyards] was unique, not only the industry but the people … it was the backbone of Collingwood … A lot of people thought the yard would open again. They couldn’t accept it. That’s how big a part the shipyards played in Collingwood … And Collingwood, in my mind, has never recovered and it never will. [Its closing] ruined a lot of families. It ruined a lot of lives.”

Underdown hung on for several more years, staying behind to disassemble the shipyards. He tore down his berth cranes, some of them were scrapped, others sent to shipyards elsewhere.

One day he went to retrieve the shipyard whistle. The mechanism and case were intact, but the whistle was gone. Sometime between its final blast and the day Underdown arrived someone had taken it. Its location remains a mystery.

“It’s hard to believe it’s been 30 years,” said Underdown. “I would walk the buildings alone with my flashlight and remember this thing that happened here or remember talking to someone there … I don’t think you’re ever over it.”

This Saturday, The Collingwood Museum is hosting the second-annual Shipyard Social. The event draws former shipyard workers together with other guests in celebrating the history and heritage of Collingwood’s shipbuilding industry and those who were part of it.

Underdown will attend again this year.

“It’s about the only time you get to see any of those guys,” he said. “I saved a lot from the yard and have given it to the museum. It’s important for young people to know what happened, to know the history.”

The event takes place at the Collingwood Museum on Saturday, Sept. 8 from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m.