This article by Carmel Mothersill, McMaster University originally appeared on the Conversation and is published here with permission.

Shortly after Russia launched its attack on Ukraine, both governments said that the Russian military had taken over the decommissioned Chernobyl nuclear power plant, the site of the world’s worst nuclear disaster. In a tweet, the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs raised fears of possible ecological disaster.

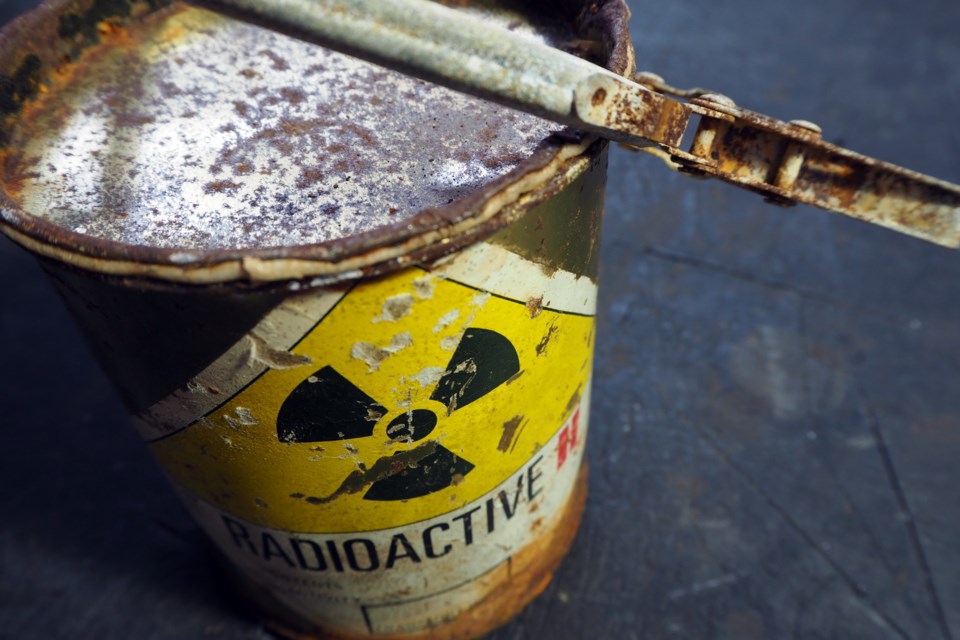

On April 26, 1986, a nuclear reactor at the plant near the city of Pripyat, Ukraine, exploded. The fire burned for 10 days, spewing a radioactive plume that stretched across Europe, as far as Ireland and Greece. The immediate area around the reactor was evacuated, and a 30-kilometre radius exclusion zone has remained in place for almost 36 years.

Access to the Chernobyl exclusion zone has been strictly controlled. The Ukrainian army typically allows only those associated with scientific expeditions or more recently, dark tourism — visiting sites associated with death and suffering — into the area.

I’ve visited the area six times, most recently in 2018, to study the impacts of long-term low-dose radiation on animals. These impacts, in humans and other animals, are of great concern and highly controversial. Much of the uncertainty is caused by the difficulty of working at sites such as Chernobyl, and the variability and complexity of the ecosystems in contaminated areas. The scientific uncertainty naturally leads to concern about whom to trust.

Elevated radiation, but still safe

Wildlife has thrived within the zone in the absence of humans. Thick forests grew up and attracted lynx, bison, deer and other animals. Wolves and Przewalski’s horses, animals that neared extinction from over-hunting and land use practices, were reintroduced, and have been thriving.

The prospect of armies bringing heavy equipment, including tanks, through an ecosystem that remains highly contaminated in some places is not good. There have already been reports of spikes in radiation readings, possibly from the heavy military vehicles churning up contaminated soil.

The International Atomic Energy Agency said on Feb. 25 that the readings are low and don’t pose a danger to the public. Still, with heavy fighting nearby, there’s always the danger of an accidental strike on the concrete shelter that contains the radiation still leaking from the reactor core.

The risks to human and ecosystem health are difficult to estimate. Given that it’s winter, most plant and animal species are hibernating, dormant or, in the case of birds, have flown south. By the time nature awakens, any elevated levels of radiation caused by vehicular movement will likely have settled down.

Russian army personnel are probably passing through the area — it’s the fastest route from Belarus to Kyiv — except for a core number of troops who will likely secure the zone, much as the Ukrainian army did. Russia suffered major contamination in areas east of the reactor, and will likely exercise extreme caution.

Effects of chronic radiation

The area is one of the few sites worldwide where scientists can collect field-based data on the effects of chronic exposure to radiation on wildlife. My own group’s work in Chernobyl seeks to understand the long-term effects of chronic exposures to low levels of radiation, as well as how these effects may be passed on from one generation to the next.

Prior to the pandemic, we were part of a multidisciplinary team monitoring levels of radioactivity and associated health effects — anemia, cancer, cataract or immune compromise — in wild vole populations. Radiation levels in the area are variable but can lead to high doses, and some voles experienced radiation rates 40 times higher than unexposed control voles.

Yet we could not say with any certainty that the health effects we detected were due to radiation exposure. This is because of all the other stressors in the environment, including predators, parasites, disease and starvation.

The health effects of low-dose radiation in ecosystems are highly controversial. Tim Mousseau, a biologist at the University of South Carolina, has reported multiple abnormalities in a variety of species, and Rosa Goncharova, a radiation geneticist at the Institute of Genetics and Cytology, National Academy of Sciences of Belarus, has found that the descendants of animals that experienced the early high-dose radiation continue to show many chromosomal abnormalities.

But others, including Mike Wood, an environmental scientist at the University of Salford and Nick Beresford, a radioecologist at the Institute for Hydrology and Ecology at the University of Lancaster, find no evidence of such effects.

Nuclear power and wildlife risks

Our own data gathered in Chernobyl in 2018 are still being analyzed, but preliminary findings reveal enormous individual variation and fail to show any clear statistically significant correlation between negative health effects and radiation dose. We consider low-dose radiation effects to be highly uncertain and influenced by other factors, such as predation or disease. This is not to say radiation is having no effect, just that assigning a level of effect to radiation is not possible.

Resolving the controversies and deciding how to interpret the results are of considerable importance. Many countries plan to expand nuclear energy production by siting small modular reactors in remote areas, and it is important to understand what the risks to wildlife might be if there were a nuclear accident or from nuclear fuel processing, uranium mining and the radioactive discharges that result from operating a nuclear power plant.

Whatever the outcomes of these studies, it is important to recognize that no one can work in the Chernobyl exclusion zone without collaborators from Ukraine who provide local knowledge, laboratory facilities, transport and sustenance, as well as help with permits. None of us knows what will happen to these collaborations that have lasted for years.![]()

Carmel Mothersill, Professor and Canada Research Chair in Environmental Radiobiology, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.