If you take a walk along the Barrie waterfront, you will notice that ice is beginning to form. If this winter proves to be an ordinary one, with the usual spells of below-freezing temperatures, Lake Simcoe will freeze over completely.

Ice fishermen, snowmobilers and other winter weather enthusiasts will be watching this process with excitement. The rest of us will beg their forgiveness for not sharing their enthusiasm. What does the lake ice offer us? Perhaps not as much as it once did.

It was not always this way.

When the community of Barrie was just emerging from the woods in the early 19th century, Lake Simcoe had already been acting as the Highway 400 of its time for centuries. Before railways or decent roads, the water was the only way to reach this region. The lake could be traversed during open water season or once the ice was solid.

Frozen Kempenfelt Bay was for years a beehive of activity. Before the advent of modern electric refrigerators, Lake Simcoe ice was highly sought after for its purity as it filled ice boxes from here to Toronto, Buffalo, Cleveland and beyond. An entire seasonal industry grew from the harvesting of lake ice.

Back in the days when winter weather was more predictable, winter carnivals were held on the frozen bay. The cold weather produced thick ice, strong enough to support thousands of people, parked cars, military vehicles and multiple sporting events all at once.

Odd as it may sound, the thought occurred to me that this annual shutting down of the majority of lake activities has been a life saver of sorts. Of course, there have been tragic mishaps on the ice, plenty of them over the years, but when the water becomes naturally inaccessible, less humans are found on it.

A story caught my eye last week. It was the tragic tale of the J.H. Jones, a tugboat built in 1888 and lost in the winter of 1906.

Georgian Bay, where the J.H. Jones once plied the waters, is a massive body of water attached to the even more massive Lake Huron. Like the other freshwater Great Lakes, Lake Huron is much like an inland sea. These vast expanses of open water allow great storms and waves to form.

Unlike our Lake Simcoe, these big lakes do not entirely freeze over. This is a bonus for the shipping industry but winter sailing is risky business for all those who step onto a boat in this harsh season.

At 107 feet in length, the J.H. Jones was considered a small vessel. She started out as a fishing boat but was soon carrying goods and passengers up and down the eastern coast of the Bruce Peninsula, from Owen Sound, over to Manitoulin Island and back.

The captain of the J.H. Jones was James Victor Crawford, the son of Irish immigrants who had first settled in Lanark County in the late 1850s.

Crawford later came with his family to Keppel Township in Grey County. He had spent his early life in farming, but, by the late 1880s, he was the owner of the Crawford Tug Co. based in Wiarton.

Crawford was an experienced mariner, a fact that matters little when a Great Lake storm begins to blow wildly. Cpt. Crawford, the crew of 13 and the 17 passengers aboard had little chance during that fierce gale of Nov. 22, 1906.

It was to be the last run of the season. It became the last run ever. The J.H. Jones left Owen Sound and was headed to Lion’s Head with passengers and a cargo of coal oil, brick making machinery, a sleigh and other goods. They made it as far as Cape Croker.

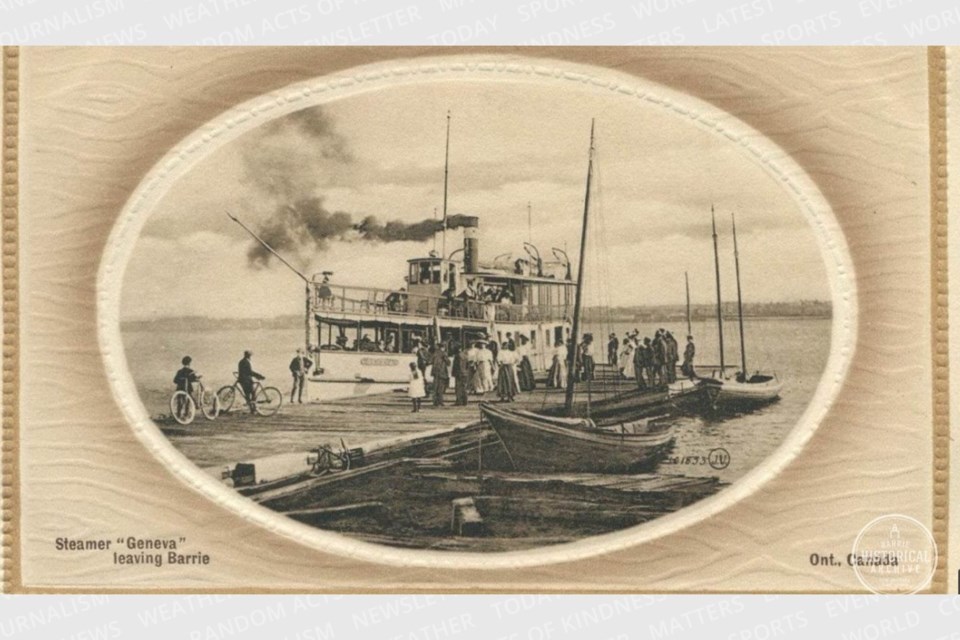

Each week, the Barrie Historical Archive provides BarrieToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past. This unique column features photos and stories from years gone by and is sure to appeal to the historian in each of us.