My daughter rents the tiniest of rooms in a narrow house near Toronto’s Kensington Market. Last spring, she gathered up a hodgepodge of mismatched discarded planters and pails, filled them with soil and placed into them the vegetable seedlings that she had been nurturing in every corner of her small living space.

These peppers, strawberry plants and tomatoes thrived outside on a brick patio in among bicycles and recycling bins. Her very first harvest was a truly exciting event.

I normally grow a vegetable garden myself and it usually includes tomatoes, cucumbers, leaf lettuce, garlic, dill and parsley. Seedlings, purchased from a chain store garden centre, are dug into a very small corner of my rather large yard.

My daughter’s shoestring, no-frills approach made me think about growing food differently and, in fact, made me realize that I could be making much better use of my resources.

In these strange circumstances that we now find ourselves in, we have moments of anxiety about our food supply system. Our concern may turn out to be largely unfounded but the idea of growing some of our own fresh produce can be both comforting and a great outdoor activity in the coming weeks of being homebound.

Although it was a different time, and the threat was then the German war machine, the idea of urban crop growing for a cause is not new. A campaign of food gardening, to better the community, came to Barrie in 1917 in the form of Victory Gardens.

“In this year of supreme effort Britain and her armies must have ample supplies of food, and Canada is the great source on which they rely. Everyone with a few square feet of ground can contribute to victory by growing vegetables.”

This ad, inserted in the Barrie Examiner of March 15, 1917, listed the “Four Patriotic Reasons for Growing Vegetables”. Home gardeners, it was suggested, could save money, reduce the cost of living, expand the supply of food available for export and save the labour of those needed to do other vital work.

The Ontario Department of Agriculture placed ads of this type in newspapers all over the province with the aim of reaching city and town dwellers. It also appealed to local service clubs to get involved and to arrange classes and lectures for the novice gardeners and to organize competitions and offer prizes for the best vegetables.

The Victory Garden movement was revived during the Second World War. This time, the program expanded beyond private back yards and included the cultivation of large lots by clubs, church groups, schools and business organizations.

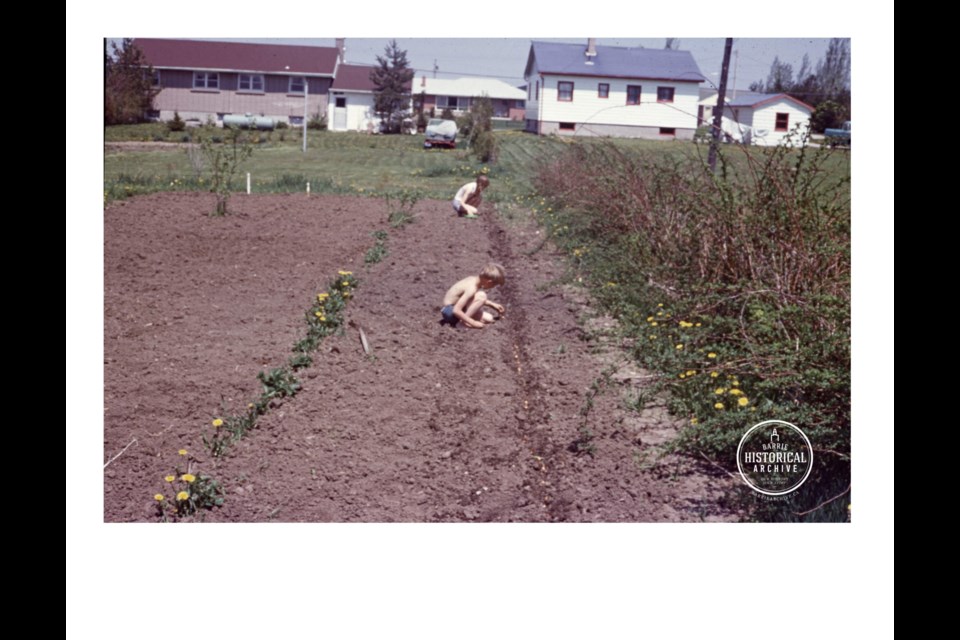

In April 1944, the Kiwanis Club of Barrie advertised free garden plots, located on the north end of Toronto Street, available to anyone who wanted one. Two acres were divided into thirty-four plots, each of them fifty feet square.

On May 15, the garden plots were ploughed and ready to be planted. All the plots were eagerly reserved by Barrie folks and were soon filled with all sorts of edible plants with potatoes being the favourite.

After the produce was harvested in the fall, the Victory Garden Committee of the Kiwanis Club held an awards night to hand out prizes to the best vegetable plots. The winners were H.R. Palmer, A.B. Cockburn, M. Chepesuik, S.E. Lewis, and Ross Allens. Some of the winners immediately donated their cash prize to the Milk Fund for Britain.

I have purchased a few packets of vegetable seeds. Now I just need to get some seedlings going!

Each week, the Barrie Historical Archive provides BarrieToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past. This unique column features photos and stories from years gone by and is sure to appeal to the historian in each of us.