While the old question might have been: "what came first, the chicken or the egg?" the new question is: "who can afford either?"

It's not so much the cost of food that is pushing almost one-quarter of Ontarians and one-third of Simcoe County residents into food insecurity, rather it's that so many incomes fall short of covering basic needs.

That's according to a Simcoe-Muskoka District Health Unit nutritionist, Vanessa Hurley, and many other health units across the province that have been watching both income levels and food costs since 1998.

"It's always been unattainable for many residents to be able to afford nutritious food, and it's not because of the cost of food," said Hurley in an interview with CollingwoodToday. "They just don't have enough money at the end of the day ... they don't have enough to meet their basic needs."

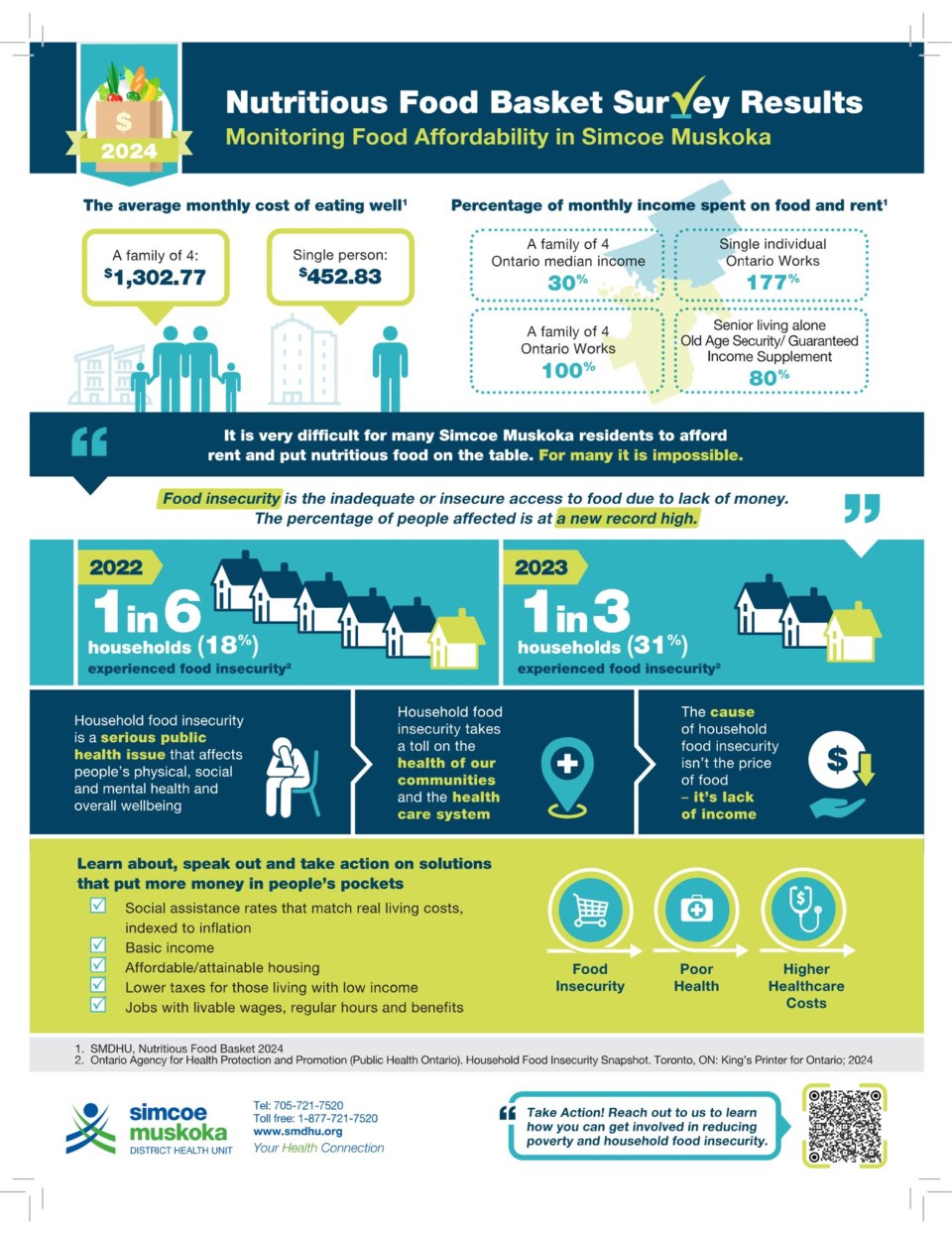

In 2023, one in three households in Simcoe County experienced food insecurity, which increased from one in six households the year before.

"It's a new record, worse than the provincial averages," said Hurley. "Many of our residents cannot afford to put nutritious food on the table, they cannot afford their rent. For many it is impossible and these are basic needs."

In 2023, 24.5% of Ontario households lived with food insecurity, which is significantly higher than the 16.1% of Ontario households that experienced food insecurity in 2021.

Public health units in Ontario have been mandated, since 1998, to monitor food affordability, specifically by relating the cost of a "nutritious food basket" to household incomes within the public health unit boundary.

The figurative nutritious food basket includes 61 items selected based on Canada's Food Guide such as vegetables and fruit, breads, cereals and other grain-based foods, milk and other dairy products, meats fish and poultry, canned beans and other meat alternatives.

In Simcoe-Muskoka the average cost of the items in a nutritious food basket per month is about $1,302 in 2024, which is up by six per cent compared to 2023. Click here for the full report.

A family of four in Simcoe County will spend at least $1,260 on food groceries in a month, and that's only for the basics -- no convenience foods, no special diets for allergies or medical conditions, and no non-food items like toilet paper, soap, and toothpaste.

"These items are whole, unprocessed foods that must be prepared," said Hurley. "It doesn't include processed foods, it doesn't include convenience or snack food, coffee, and all those extra things like personal care items and cleaning supplies."

It's inadequate, too, at capturing food costs for religious or cultural groups with different food requirements, and it doesn't include Indigenous food traditions or procurement practices.

Allergies or medical conditions, such as celiac disease, would also significantly impact a family's food purchases and, thus, the cost of their monthly grocery bill.

Also excluded from the cost calculation is infant formula, which according to the Public Health Agency of Canada is a $200+ monthly expense.

To build their annual report, Simcoe Muskoka District Health Unit staff – dietitians and public health nurses – visit more than 14 grocery stores in the region to look at the cost of the same 61 items and average that cost out across all the stores.

Hurley says the result is a modest estimate, and it shouldn't be used as a budgeting tool.

"We're basically monitoring it in the sense of putting it into the whole context of the bigger picture that, yes, food costs are high ... but they've always been high," said Hurley. "It's just basically to paint the picture that families just don't have enough money to buy food."

The health unit's report dives into income data to pair with the average cost of a nutritious food basket, revealing that any family or individual in Simcoe County or Muskoka on Ontario Works does not take in enough money to pay for rent and food. Disability payments and minimum wage incomes aren't much better.

An adult in a bachelor apartment with income from Ontario Works would need 177 per cent of that income to pay for just basic, nutritious food and rent.

A family of four with one full-time minimum wage income would take in about $4,507 per month according to the heath unit's report, of that, at least $1,303 would be spent on basic, food-only groceries.

The health unit report allocates another $1,611 on rent, but that's underestimated, acknowledges Hurley.

If the family of four with a single minimum wage income could find a place to rent for about $1,600, that still only leaves about $1,500 a month for basic needs.

"People talk about cutting food costs down and budgeting, but that's not the answer," said Hurley. "We basically need more policies in place and solutions to put more money in people's pockets."

Food insecurity refers to inadequate or insecure access to food due to lack of money or income.

"There's a broad definition of food insecurity, it can be from moderate to severe," said Hurley. "It can be worrying about running out of food and compromising on quantity and/or quality and then, in severe cases, you're skipping meals, you're going days without food, which we see happening in a lot of households."

She added that the health unit has seen mothers go without eating to feed their kids.

"More people are impacted than we realize," she said.

The impacts also go beyond the hungry families.

"We see it as a very serious public health issue that affects individual physical health, causing a greater risk of chronic diseases, their social health, and their mental health, and just their overall wellbeing," said Hurley.

Children, in particular, are more susceptible because inconsistent and inadequate access to food can cause physical illness and disease, behavioural issues, and negative impacts to their mental health, their ability to learn, and their social development.

"It really impacts the overall health of our communities because we have communities that are not thriving," said Hurley.

Ultimately, food insecurity also increases the costs of healthcare and other similar resources as people's physical and mental health suffer.

Grey-Bruce

Results from 2024 gathered by Grey Bruce Public Health show are like brushstrokes on the same picture as the one painted by the Simcoe Muskoka District Health Unit.

The Grey-Bruce report determined the cost of groceries for a family of four in Grey-Bruce is around $298 a week or $1,250 a month. For a single adult, the cost is about $434 a month based again on the nutritious food basket ites.

Both estimates are only one per cent higher than they were in 2023, but it's still higher than many people can afford.

"Based on those costs, a family of four on Ontario Works would have to spend nearly half (43%) of their monthly income on food to meet Canada’s Food Guide recommendations," states a news release from Grey Bruce Public Health released at the end of 2024. "After covering only rent and groceries, they would be left with only $314 a month to cover all other expenses, including utilities, transportation, and medications."

Single people on Ontario Works actually took in less than they needed for just the cost of housing, which is about 107 per cent of their income. That left zero dollars for food each month.

In Grey-Bruce region, it's estimated that almost one in five households struggle to buy the food they need, which puts them in the category of food insecure.

The Grey Bruce Health Unit, like Simcoe-Muskoka, maintains that food insecurity is not caused by rising food prices, but rather by incomes that are too low, which forces families "to make impossible choices between shelter, food, medication, transportation, and other needs."

Solutions

For people like Hurley, who have been watching food insecurity numbers in her own region climb to historic levels, the answer is not cheaper or even free food, it's more money in pockets.

"In Canada we have a long-standing history of food banks and food charity and those are wonderful and needed, especially in times of emergencies, but household food insecurity is only getting worse, and so it's not decreasing the rates," said Hurley.

"The solution is increasing people's income, so these are big, big policy changes."

She said there are things to be done at all levels of government, more so at the highest levels, such as increasing social assistance rates to match real living costs indexed to inflation, jobs with livable wages regular hours and benefits.

Contract work, too, can come with some food insecurity because it can be precarious income.

"There's a lot of talk about guaranteed basic income as well," said Hurley. "Hopefully, the more we advocate for that, and with some political changes, maybe we'll see some momentum."

"Honestly, a guaranteed basic income is probably the answer, and looking at more affordable, attainable housing, lower taxes for those living with low income."

Municipally, things like subsidized recreation programs and help for people to file their income tax benefits can make a difference in helping families make their incomes go further.

"The answer is more income," concluded Hurley. "People just don't have enough money to meet their basic needs."

As part of the health unit's Chronic Disease Prevention Program, Hurley advocating for higher incomes is a priority for her and the whole team. She encourages community partners and municipal leaders to work with them on solutions.

She believes it is collective action, advocacy and awareness that will help move the needle on better systems and policies to help people afford rent, groceries and their other basic needs.

"We can't afford not to do anything," said Hurley. "We can't afford just to let this happen in our communities."