In Collingwood, they have found friends and family. And while this town wasn’t their first stop in Canada, it was the first where they found kindness.

Alaadin Ibrahim and his wife, Cemile Ibi, with their three children Mustafa (17), Avjin (14), and Muhammed (8), owned and operated a bulger wheat farm in Syria, near the Turkish border in a town called Kobani.

“Syria was good,” said Avjin. “But there was war on every side and they ended up in our city. At 10 a.m. we heard war and people screaming.”

The family hopped into a car with their cousins and fled for the Turkish border. That was about four years ago.

“We left everything,” said Avjin. “When we were running and we looked back, we could see fire.”

The cruelty began at the Turkish border, where bombs exploded behind them and gas bombs went off in their faces.

“The Turkish people were spraying people to get dizzy, and they had all the things to make it hard to cross,” said Avjin, who was about 10 at the time her family fled.

She was separated from them at the border as they all ran to find a safe place. “They were not nice, they would not let the Syrian people come in.”

Muhammed, just 4 years old when they left home, listened to his sister tell of their flight.

“Wow, I’m learning so many new things,” he exclaimed.

Avjin said her family was one of the lucky ones; their Kurdish background and family in Turkey meant they could rent a house.

“The Turkish people, when a Syrian would say we want to rent the house, they would say, ‘get away, we don’t want to rent you the house,’” recalled Avjin. “People would have to sleep in the parks. They were mean, they wouldn’t let people in.”

Since the Ibrahims spoke Kurdish, Alaadin and Mustafa (13 at the time) were able to find work.

“My brother would go to work all day for $5 or $10,” said Avjin. “My dad worked all day running from this house to that house for $10.”

In Syria, Alaadin was a languages teacher, a farmer, and a farm equipment mechanic. He found electrical work in Turkey.

A refugee claim didn’t cross the family’s mind.

“We didn’t know about these things,” said Avjin, who attended school in Turkey, though her brothers did not. “We were just living there like a regular life … my grandparents were sick, my mom was sick.”

Cemile is in a wheelchair, and it was her wheelchair that sparked a conversation at a dinner table. Someone told them she could get special permission to go to Canada because of her disability.

About six months later, the family received the papers they needed to leave Turkey and go to Canada. That was two years after they left Syria.

They took a 20-hour bus trip to Istanbul, stayed there for three days, then flew to Germany before flying to Toronto.

They arrived in Toronto with friends and fellow government-sponsored refugees. At the airport, they learned their friends were going to Windsor while they were going to Saskatoon. They were each handed winter clothing.

Muhammed piped up, “I still have my boots at home!”

“Nobody told us what was going to happen. The only thing they told us was, ‘you’re going to the coldest place in Canada,’” said Avjin.

They arrived in Saskatoon a few days later. The government-assigned aid spent 15 days helping them with paperwork, then, said Avjin, left them to fend for themselves.

Because the Ibrahims arrived in May, there was no school for several months. English classes were also on break, and aside from setting them up with an apartment, the Ibrahims were left alone in a new country and city they knew nothing about.

“They didn’t treat people the right way,” said Avjin, adding her family stayed in their apartment for three months without television or Internet and without help to get to a market or find out about what help was available to them.

“I don’t think that’s right, you just bring a family into a different place where they don’t know what they’re doing and you just say, come to a meeting later. No language or anything … We came in May, had three months off school. In these three months, nobody taught us, nobody asked us where you are at … you’re like a dead person.”

According to the Government of Canada website, government sponsorships of refugees like the Ibrahims is done through the Resettlement Assistance Program (RAP).

The support services listed on the website include things like a greeting at the airport, temporary housing, help with registering for federal and provincial programs, and orientation to the community.

The RAP provides income support to the tune of a one-time household start-up allowance and monthly income support payments based on the social assistant rates of the province where the refugees settle. Financial support can last up to one year or until the refugee can support themselves.

However, Alaadin, Cemile, and Avjin didn’t get the communication promised to them. Whether through error, miscommunication, or apathy, they were left without support, and without knowing what was supposed to happen next.

The family had no friends. They said they asked people in the street for help - finding a store or a meeting location - and they were ignored.

Cemile waited for language training for six months. Her first MRI was 10 months later, even though the reason for their refugee sponsorship was her health.

She had lost function in her arms, and endured severe, chronic pain. A doctor told her “they would get better on their own,” and she was sent home.

When Avjin was sick for a week and Alaadin pleaded for help from doctors and the emergency contacts provided by the government sponsorship office, he was told to go home and wait for her to get better.

“It’s really hard when you come and you don’t have anyone standing with you,” said Avjin.

Nearly immediately, the Ibrahims decided they didn’t want to stay in Saskatoon. They figured they would move to Windsor, where they knew their friends had been placed. They also had cousins, the Bozan family, who had come to Collingwood as a privately-sponsored refugee from Syria in 2016.

On April 1, 2017, the Ibrahims moved to Collingwood.

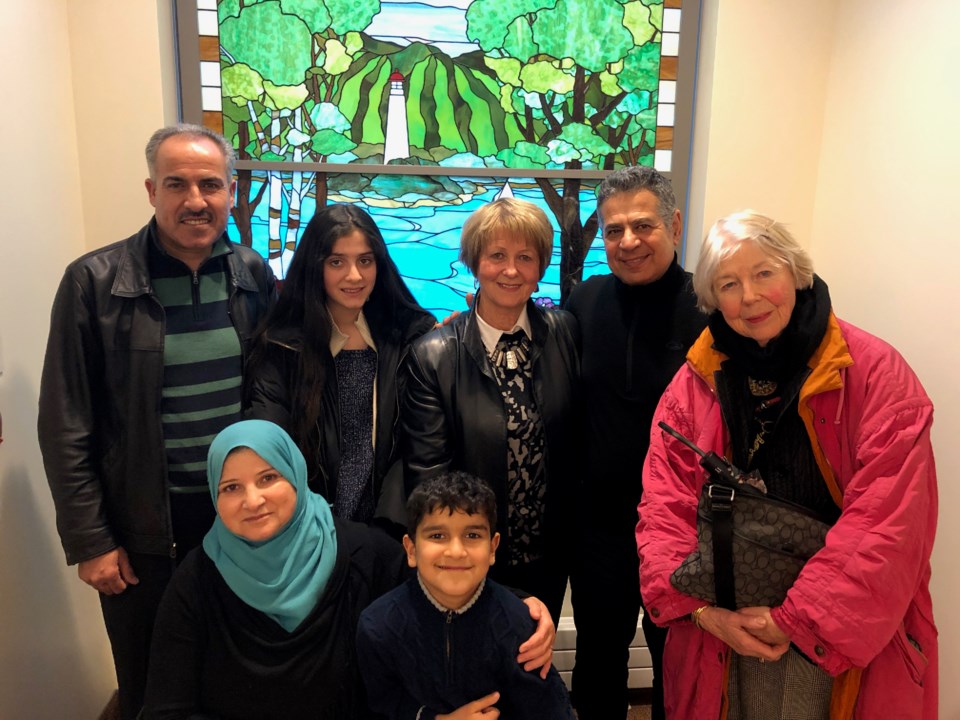

Though housing was an issue - they moved five times in the first month - they were welcomed by volunteers with the sponsorship committee. They had English classes scheduled by April 2, and two volunteers, Sharon Stewart and Marc Suood, arrived at their door one morning with an offer to take them shopping for groceries.

Avjin first became a refugee at 10 years old. Now, at 14, with good and bad experiences and a view of both public and private sponsorship, she sees a clear need for improvement.

“The most important thing to me is better communication,” said Avjin. “Like … be nice. Even if you don’t understand something, try to make it seem like you’re helping. You can do something nice about it.”

Volunteers and business partners of the Collingwood Syrian Refugee Committee have done just that. They’ve communicated with the Ibrahims and they’ve reached out into the community to find ways to help.

Cemile has had successful surgery and regained the use of her arms.

All five members of the family get regular English as a Second Language training - though Avjin would like to see it integrated more into her high school classes.

The kids enjoy sports like soccer and snowboarding.

“Now it’s good,” said Alaadin. “We have more friends. If I call anyone, they help. In Saskatoon, I didn’t find that. It’s a good place for everyone. Everyone is happy.”

Suood has been a volunteer with the committee since its inception, having been recruited for his ability to speak Arabic. He acts as a translator where English communication fails.

Both Suood and Stewart were given the Order of Collingwood at this year’s January ceremony.

During their acceptance speech, Stewart told the crowd through the efforts of all the volunteers on the committee, they’ve been able to help six refugee families move to Collingwood.

“Collingwood is a volunteer community, and that’s what we’ve found,” said Stewart.

The committee assists with private (church) sponsorships of refugees from Syria to Collingwood, which includes meeting them at the airport, helping them find a home, financial help, transportation, and arranging English as a Second Language classes.

The committee has also worked with local businesses like the Westin at Blue Mountain to find employment for refugee families.

Alaadin works at the Westin.

“When we came to Collingwood they said even if you don’t speak the language, you could work,” said Avjin. “That’s an awesome opportunity for people to work. Other cities they don’t offer that.”

Stewart, a retired teacher, said jobs and education have been the programs she’s seen help refugee families the most.

“We are blessed with having a small community and the church sponsorship, which is ideal, because that comes with a support committee,” said Stewart. The committee extended its help, programs, and services to the Ibrahims as well. “With the families arriving, I wanted to make sure the children had the best opportunities.”

Suood is from Iraq, but he left during the war between Iraq and Iran in the 1980s. His family sponsored his education at the University of Belgrade in Serbia.

He meets each family and gives them his number for emergencies. He’s particularly enjoying the Middle Eastern cooking Cemile inevitably prepares for every visit.

“You don’t leave the house without food or drink,” said Avjin, adding her mother’s passion is cooking. “That’s our culture, that’s how we do it. When people come to our house, they don’t get out until they eat.”

“I learn a lot from every family,” said Suood. “They’ve taught me a lot from all the years I’ve been with them. Sometimes when I go away on a trip, I miss them.”

Avjin said without Steart and Suood, her family wouldn’t have stayed.

“She’s like our family,” said Avjin. “You need family to make you feel good and loved.”

Alaadin said he and his family feel settled. He has no plans to go back to Syria, even if the war, now going on nine years long, ended.

“Here, it’s like living in my city in Syria,” said Alaadin. “I see (Stewart and Suood) as father and mother for my kids. If we died, no problem, I know I have a good father and mother for my kids. In Saskatoon, there was no one. Here, everyone is good.”

If you’d like to help as a volunteer, donor, or supporter of the Collingwood Syrian Refugee Committee, you can find more on their website here.