This article, written by Liam Midzain-Gobin, Brock University and Heather Smith, University of Northern British Columbia, originally appeared on The Conversation and has been republished here with permission:

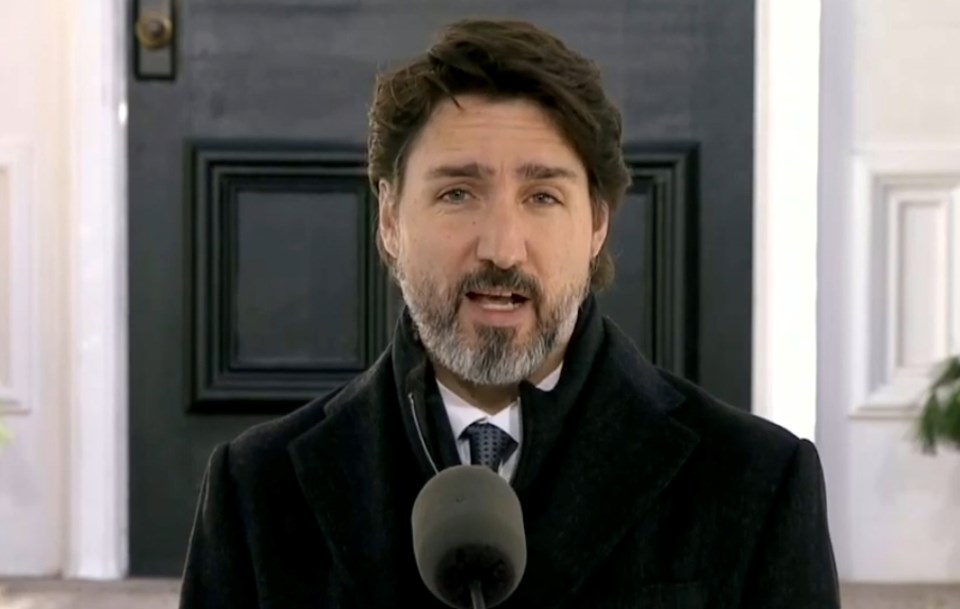

At a press conference on March 9 after Oprah Winfrey’s interview with Prince Harry and Meghan, the Duke and Duchess of Sussex, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was asked about his commitment to the monarchy and, in particular, whether it sat uncomfortably beside his stated desire to “dismantle colonialism in this country.”

In response, Trudeau acknowledged:

“There are many institutions that we have in this country, including that big building right across the street from us, Parliament, that has, and is, built around a system of colonialism, of discrimination, of systemic racism.”

During that same press conference however, when identifying solutions, Trudeau’s words changed. He began using the type of language we identify in a recent paper as “reconciliation lite.”

In analyzing statements made by past Canadian leaders to the world, we found that their language promotes a myth of Canada as a non-colonial power. We use reconciliation lite to describe a narrative that recognizes the need to correct past harms, but sees this as a problem solved by multiculturalism or legal rights. This narrative continues to centre settlers and their interests, and is not a move to return land or authority, or rebuild meaningful relationships between the Crown, Canadians and Indigenous peoples.

Trudeau’s response reflects this. Instead of continuing to acknowledge colonialism, his focus shifts to systemic discrimination. He said:

“The answer is not to suddenly toss out all the institutions and start over. The answer is to look very carefully at those systems and listen to Canadians who face discrimination every single day, and whenever they interact with those institutions, to understand the barriers, the inequities and the inequalities that exist within our institutions that need to be addressed, that many of us don’t see because we don’t live them. That’s what fighting systemic discrimination is all about. Listening, learning and improving, and transforming our institutions.”

By identifying the need to tackle systemic discrimination instead of colonialism, Trudeau is reinforcing an established idea in Canadian politics: that colonialism is history.

This idea is powerful. It offers some recognition of ongoing cultural harms today while shifting our attention away from colonialism’s structural nature, pointing instead to how we must end discrimination as racism and intolerance.

You can’t put a time-stamp on colonialism

As two settler scholars we are struck by the way colonialism is time-stamped as a historic phenomenon, effectively denying our settler colonial present. This exemplifies what scholars Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang call “settler moves to innocence.” These moves are an evasion of responsibility for the way settler colonialism today continues the project of Indigenous dispossession, whether that be of lands and waters, relationships, or as importantly, political authority.

Narratives that historicize colonialism are not new. Canadians and our leaders have a long history of identifying colonialism at home with British imperialism.

For example, former prime minister Stephen Harper’s apology for the residential school system did not include references to colonialism when admitting the “failings” of this country. He would go on to say that Canada itself has “no history of colonialism” at a 2009 G20 meeting. This narrative crosses parties, with Trudeau’s 2017 speech at the United Nations also identifying only “historical wrongs” and a “legacy of colonialism.”

Rather than following the lead of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and more recently the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Women and Girls, leaders insist that today Canada is not a colonial power. With this they participate in “maple washing.” By promoting the myth that Canada is morally superior, they are washing their hands of negative historical and contemporary actions, using the language of reconciliation to insist that we are a human rights leader at home and abroad.

Absolving responsibility

This is an attractive self-image. And in some ways we’re starting to see movement; the gap between rhetoric and reality is narrowing.

Focusing on systemic discrimination can bring real benefits, as we are seeing in some public health responses to the pandemic: recognizing medical discrimination has meant Indigenous communities have been among the first to receive vaccine doses. This offers protection to communities that have been disproportionately affected and had to create their own solutions.

By time-stamping colonialism however, Trudeau, and the many Canadian leaders before him, are absolving our governments of its responsibility for the structural nature of contemporary settler colonialism that continues through government policy and practice. They simultaneously refer to the need to advance reconciliation while reinforcing assumptions of settler sovereignty, and participate in the ongoing dispossession of Indigenous lands and waters. Discrimination and settler colonialism, while connected, are not the same thing.

Not understanding ourselves as a colonial power means ongoing conflict between the government and Indigenous nations.

Before and during the pandemic we have been caught up by news of governments seeking to impose their authority over Indigenous nations practising their rights to self-determination. From Sipekne’katik First Nation standing up for their treaty rights to earn a moderate livelihood, the Wet’suwet’en defence of their lands and people to 1492 Land Back Lane on Six Nations territory.

It doesn’t stop there

We have seen the continuation of the government’s efforts to avoid paying compensation or equal support for First Nations child and family welfare and their failure to fulfil commitments to end long-term boil water advisories in First Nations communities. There is a common link between these cases: an unwillingness by the Canadian government to move past a colonial relationship with Indigenous nations.

This starts with acknowledging our colonial present.

Ultimately reinforcing a discursive move to reconciliation lite allows the government to maintain the settler whiteness of our colonial structures and relationships into the present day, while professing to be working to eliminate systemic racism and discrimination.

In doing that it undermines the opportunity to build a decolonized, nation-to-nation relationship between Indigenous nations and the government in the type of conciliation that is required.![]()

Liam Midzain-Gobin, Assistant Professor, Political Science, Brock University and Heather Smith, Professor of Global and International Studies, University of Northern British Columbia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.